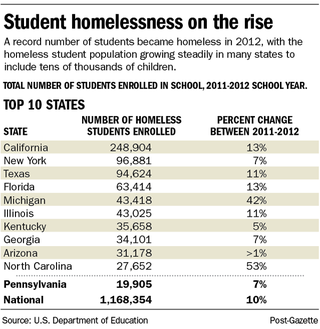

Source: Pittsburgh Post-Gazette Author: Amy McConnell Schaarsmith A record number of public school students have become homeless in Pennsylvania and the nation, putting more than 1.1 million children at increased risk of falling behind, dropping out and ultimately joining either the criminal justice system or the welfare system, according to education officials and advocates for the homeless. In Pennsylvania, the number of homeless K-12 students increased to 19,905 in 2012 from 18,531 the previous year, an increase of 7 percent, according to data released recently by the U.S. Department of Education. In the nation, the number of homeless students increased to 1,168,354 from 1,065,794, an increase of 10 percent, with 43 states reporting increases from the previous year and 10 states reporting increases of 20 percent or more, the department reported.  In Allegheny County, more than 1,700 school-age children were homeless at some point last year, said Bill Wolfe, executive director of the Homeless Children's Education Fund. Including preschool-age children, approximately 2,500 local children were homeless, he said. The increase in the number of homeless children, like the increase in the homeless population itself, began with the recession in 2007 and has continued since then, he said. In many cases, he said, both parents are working, but their jobs are minimum wage positions with no benefits and often part-time hours. "That combined income still isn't enough to rent an apartment, to come up with a security deposit and first month's rent, so they're in shelters or doubled-up situations or living night-to-night in cheap motels throughout the community, and then we have people living in their cars or vans," said Mr. Wolfe, whose organization helps support the education of homeless children throughout Allegheny County. "People talk about how things are getting better, the economy is getting better, the stock market is getting better, but for this segment of the situation, as the numbers show, the economy is not getting better." There are even more homeless children than reported, he said, because many homeless parents mistakenly think child welfare workers will take away their children if they identify themselves as homeless. That is not the case, he said. And children who experience homelessness without appropriate support are 60 percent more likely to drop out of school than those in a stable environment, he said. "If we lose a child that way, the worst part is the loss of a life, but the other side of it is that it's a loss to us and to our children, because most go in one of two directions -- the criminal justice system or the welfare system," Mr. Wolfe said. He said the average age of students living in shelters is 7.6 years -- almost exactly the age by which children need to have learned to read in order to keep up with lessons taught in upper elementary school and the higher grades. In 17 of the 27 shelters in Allegheny County, the group has created learning centers with a designated place to study, a computer and books. Throughout the county, the group has arranged for former teachers and university students seeking teaching degrees to tutor homeless students at shelters after school. For homeless children, keeping up with schoolwork amid chaos -- the entire family living in one bedroom of a relative's house, or in a different motel every night, or in the family car -- can be a struggle, he said. "Can you imagine getting homework done, getting a good night's sleep?" Mr. Wolfe said. For many students, education officials said, one of the main challenges to remaining in school is transportation, despite a federal requirement that districts provide transportation for homeless students to attend school even if those students have moved to a different area. Usually, the child is bused back to his or her usual school unless that would create a safety risk, said Janet Yuhasz, the district's liaison with the federal government on homeless student transportation. "For children who are undergoing a situation of homelessness, their world has flipped inside out, and the more we can keep the situation stable on the school end, the better," she said. "School is reliable, predictable and comfortable, and at least during an 8- to 9-hour part of their day, they're in a stable situation." Without that stability, failure can be etched into the student's future as early as sixth or seventh grade, said Judy Eakin, executive director of The Hearth homeless shelter in Shaler. Moving four or five times a year puts children behind their peers academically, making their experience of school one of frustration and failure, and often prompting them to drop out later, she said. "The way to succeed in this society is with an education," said Ms. Eakin, whose shelter houses approximately 20 women and their children. "So if you don't complete high school, what chance do you have to go any further as an adult, to be able to pay taxes and pay rent?" Amy McConnell Schaarsmith: aschaarsmith@post-gazette.com or 412-263-1719.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Get News Updates!Categories

All

Archives

February 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed